An Overview of Vowels (and consonants)

For the Singer … And the choir

A practical primer

by Stuart Hunt

The singer lives or dies on vowels

– Vocal proverb

As conductors and artists, it is incumbent upon us to help young or learning performers and students to communicate text…with clarity and expression. That is only possible once the basics of diction, no matter in what language we sing, are:

- Mastered

- Agreed upon, so that the singers both perceive and elocute with unanimity

- Regarded with precise rhythmic accuracy

A topic of discussion among us is: “If I require the singers to sing everything in unison, won’t that take away from the individual voice and effect the richness of the choir?” It certainly can, but that should not diminish the importance of unison considerations:

UNISON:

- Pitch

- Rhythm

- Phrasing

- Dynamics

- Vowels

- Consonants

To be sure, this is a vast topic, and many of the components require much more space. That is the stuff books are made of. But let’s just start with

Basic Terms

A primer

ARTICULATION

is the process by which words and sounds are formed when the lips, tongue, jaw, teeth, and palate adjust the air and sound coming from the vocal folds. In the instance of musical clarity, it relates to the production of successive notes. Its importance relates to the ability to produce sounds, words and sentences which are clear and can be easily understood and interpreted by others in order to be able to express basic thoughts and emotions.

ALLITERATION

The occurrence of the same letter or sound at the beginning of adjacent or closely connected words.

(Sheep should sleep in a shed)

ARTICULATION

relates to the formation of clear and distinct sounds in speech, and, musically, clarity in the production of successive notes.

COHERENCE

“To stick together.” The quality of being logical and consistent and flowing smoothly from one idea or sentence to the next. Musically it deals with successfully communicating text.

ELLUCIDATION

To make something clear enough to understand. For singers, this connects most of the terms listed here.

ENUNCIATION

The act of pronouncing words. The slight difference between pronunciation and enunciation is that pronunciation is the act of making sounds or articulating words while enunciation is the way of articulating words clearly and distinctly according to the rules governing the language.

ELLOCUTION

Elocution refers to the manner of speaking, specifically the skill of clear and expressive speech. The main difference between elocution and speech is that speech is a spoken expression of ideas and opinions whereas elocution is the manner of delivering ideas, thoughts, and opinions. Yes, it too relates to enunciation, elucidation, and all topics discussed here.

PHONATION

The actual production or utterance of speech sounds. The larynx contains the vocal folds which actually produce sound. Specifically, sound is produced by an air stream from the lungs, which goes through the trachea and the oral and nasal cavities. It involves four processes: Initiation, phonation, oro-nasal process and articulation.

PHONICS

involves matching the sounds of spoken English with individual letters or groups of letters. For example, the sound k can be spelled as c, k, ck or ch. English has many different pronunciations for the same spelling. Think “ough” and its many iterations.

PRONUNCIATION

Basically, how you say a word and how it sounds. Differing from enunciation (see above) in that it may have cultural, regional, and geographical implications. The classic example is from the Fred Astaire song

“Let’s Call the Whole Thing Off:”

You say eether and I say eyether,

You say neether and I say nyther;

You like potato and I like potahto,

You like tomato and I like tomahto;

So, if you like pajamas and I like pajahmas,

I’ll wear pajamas and give up pajahmas

UTTER

To speak or to articulate a sound. If you utter something, you give it voice.

In the Introduction to Nicola Vaccai’s “Practical Method of Italian Singing” he elucidates for the student of voice:

“….in order to give, as far as possible, an idea of the right manner of pronouncing in Singing, and to indicate how one should expend the whole value of one or more notes on the vowel of the Syllable, uniting its consonant to the next Syllable following; by this practice also the Pupil will gradually be taught to sing Legato – an art however, which nothing but the voice of a skillful Master can communicate perfectly to the learner.”

For example, the phrase “Four score and twenty years ago” would, in Vaccai practice be enunciated and sung:

“Foh rsco ra ndtweh tee yea rsah go”.

Notice, all of the final syllables end with a vowel, or, simply put, are sung with long vowels, short consonants, using the consonant to change to the next vowel or syllable. Of course, where we resonate those vowels is part of tone production, and that is the stuff of great vocal coaches. We also recognize that as important as the vowel is, it is the job of the consonant to provide clarity and context.

DIFFERENCES BETWEEN ENGLISH AND AMERICAN PRONUNCIATION

American (a form of English) is a difficult language in which to sing because American speech depends greatly upon cultural understandings. In my experience, American tends toward run-on speech and depends upon cultural understandings and can be, well, quite lazy. E.g., the American version of “Afterthegamewe’regonnagoandgetsomepizza…..wannacomealong” in English would be communicated: “After the game several of us are going to a pizza restaurant. Would you like to accompany us?” Exchange students, having learned English have, sometimes, a significant adjustment to learn American. If you don’t believe that, look at the MASSIVE explanation found on

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/American_and_British_English_pronunciation_differences

My advice: get a LARGE mug of tea before opening this site.

Dr. Geoffrey Boers (Choral Chair, University of Washington) suggests treating sung English as a “foreign language” so that the singers treat it as such with effort and changing their sound. Also, much, or most, of what really affects the vowel is what’s going on inside. Most conductors and singers focus on what we can see (jaw, lips), but tongue and pharynx play a huge role in both articulation and elucidation.

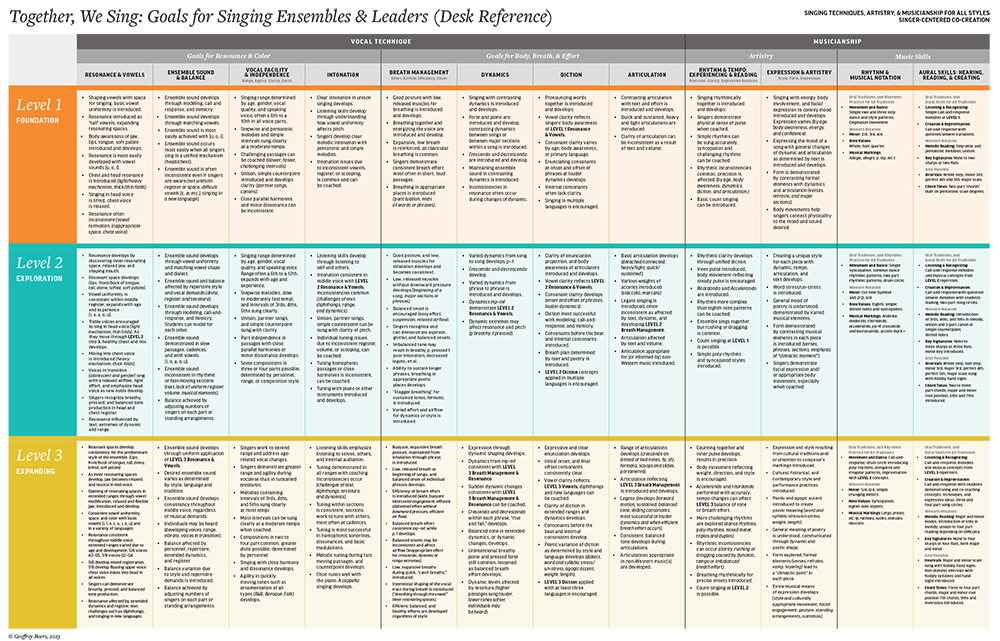

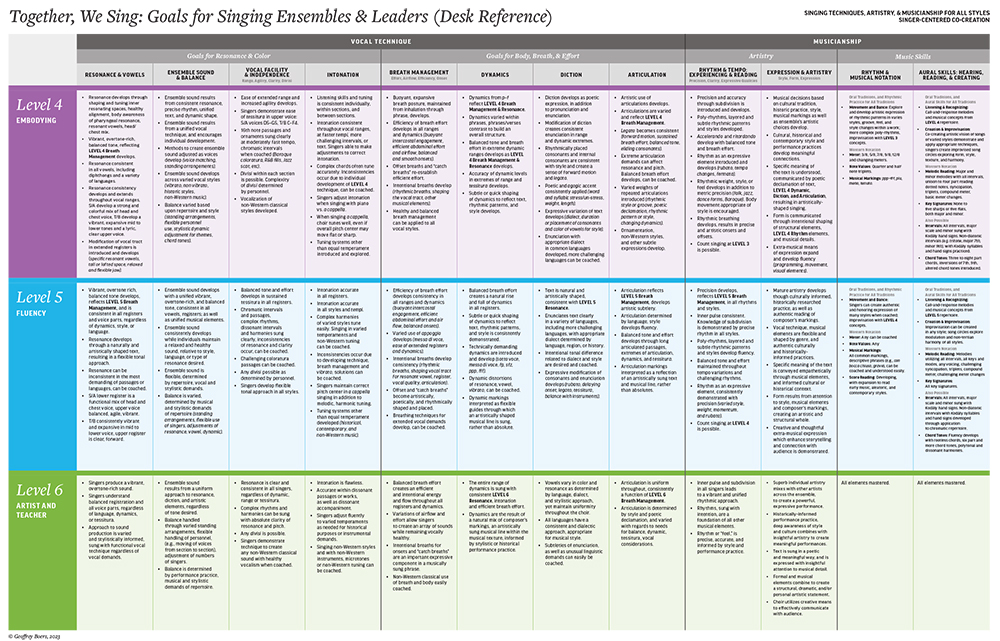

Dr. Boers’ “Together, We Sing-Pathways for Group Singing,” formerly known as CLaS, Choral Literacies and Skills, has been re-tooled and updated to being rich and diverse methods and skills to an even wider range of singer and teachers!

It is FREE to you. Click here to order:

Seasoned professionals know that failure to master vowels and consonants relegates to the listeners the unwanted task of trying to figure out what the singer(s) are singing. And conductors wonder why audience response was so tepid!

Our artistic responsibility can then be complicated by:

- Acoustics of the performance venue

- Choralography or movement by the choir

- Lighting (shadows on faces so that the mouths are obscured)

- Room temperature

- Attitude of the choir

- Engagement of choir and conductor

- Time of day

- MANY other factors

There are tools for the singer(s):

- Understanding and acceptance of their individual responsibility

- Preparedness to adapt to the vicissitudes of the above

- Awareness that, usually, the performance venue is NOT like the rehearsal venue. But, awareness can guide us.

INTERNATIONAL PHONETIC ALPHABET (IPA)

You ask: Why should I invest time in IPA? Really. After all, there are 107 letters, 52 diacritics, and 4 prosodic marks. Fair question. We could start with the purpose of IPA, which is to provide a standard set of symbols that are used to represent sounds so that the same symbols always represent the sounds, even to people from different language backgrounds.

Oh, you mean by understanding IPA I could more easily understand the sounds of Hungarian, Polish, Hebrew, Russian, Spanish, Italian, Chinese, etc., inform my students, create unison concepts, and save rehearsal time? Maybe. If you actually visited the Wikipedia site above, you would be overwhelmed. But if you did your score-study and related ANY language to IPA, you would then have common ground. There are, of course, sounds in other languages not in IPA, but not many found in choral literature. IPA will be covered in a subsequent blog.

DIPHTHONGS AND TRIPHTHONGS

Simple definitions.

DIPHTHONG:

A sound formed by the combination of two vowels in a single syllable, in which the sound begins as one vowel and moves toward another (as in coin, loud, and side ).

www.cdl.org lists ow, oe, oo, ue, ey, ay, oy, oi, au, aw. The important thing to remember is that a digraph (a combination of two letters representing one sound, as in ph and ey) is made of two letters, and although the letters spell a sound, the digraph is the two letters, not the sound. When teaching reading, the two vowel sounds most commonly identified as diphthongs are /oy/ and /ow.

TRIPHTHONG:

A union of three vowels (letters or sounds) pronounced in one syllable. Somewhat debated as in some pronunciations of our: ah oh oo , or eye: ah uh ee.

www.morewords.com defines it as “A combination of three vowel sounds in a single syllable, forming a simple or compound sound; also, a union of three vowel characters, representing together a single sound; a trigraph; as, eye, -ieu in adieu, -eau in beau”. www.thefreedictionary.com says “There are three triphthongs that are generally agreed upon in American English: /aʊə/ (“ah-oo-uh”), /aɪə/ (“ah-ih-uh”), and /jʊə/ (“ee-oo-uh”).

I hope you find this information somewhat helpful and able to stimulate a discussion with colleagues. It is THE substance with which we communicate ideas worth communicating….and,

IPA is not as inscrutable as you might imagine. Stay tuned.